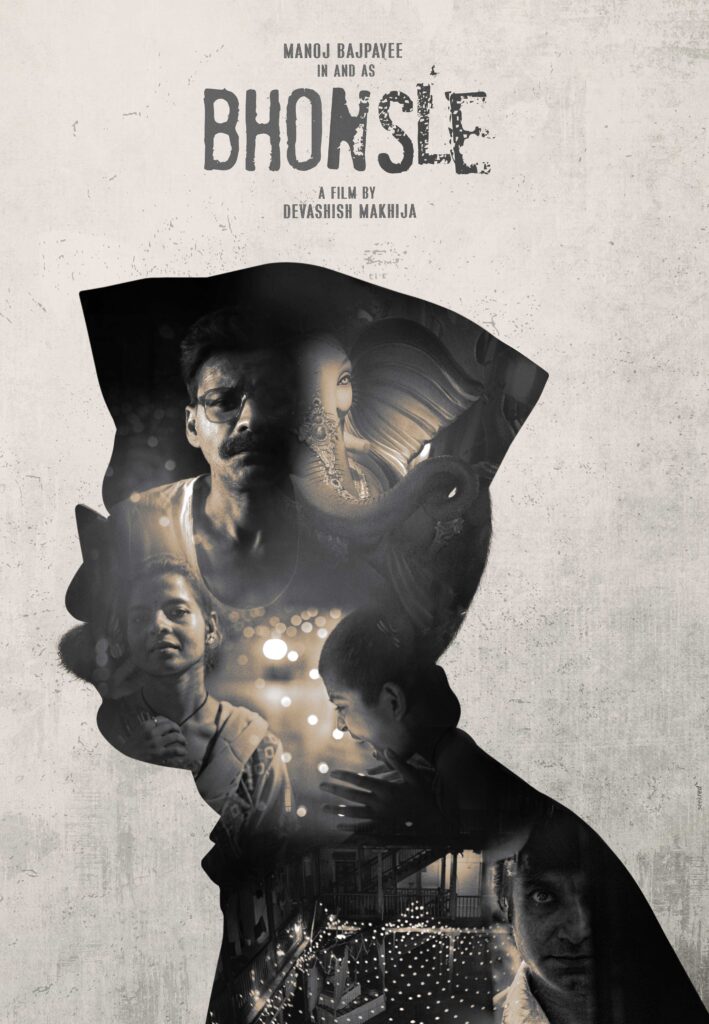

Devashish Makhija is a critically acclaimed writer-director of multiple award-winning films, including feature films like Joram (starring Manoj Bajpayee), Bhonsle (starring Manoj Bajpayee) and Ajji; and short films like Taandav, Agli Baar, Cycle, Cheepatakadumpa and others. He started his career as a researcher and assistant director on Anurag Kashyap’s feature film, Black Friday. He is also a bestselling author for numerous children’s books.

In this Interview, Devashish delves into his filmmaking career, his filmmaking choices, regrets, the state of the Indian film industry and much more. Check out the Full Interview below.

Talking Films: You have a bachelor’s degree in Economics. What made you develop the interest to pursue a filmmaking career? Was there a specific moment when you were like “I need to make films”, “I have to make films”, this is what I want to do with the rest of my life?

Devashish Makhija: Infact, even with Economics, I didn’t know that I wanted to study Economics. I didn’t have Economics in school and I don’t know why I did Economics in college. So, I have been a very confused person ever since I was probably 6 years old. So, even after I finished graduating in Economics, I did my Master’s for a couple of weeks. Then, I dropped that and I was a journalist for a couple of months after which I joined Advertising as a copy writer. From Advertising, I became an Art Director and started doing graphic design. I dropped that and I just kept trying all kinds of things. But, I had not considered cinema as I was not a ‘Movie Buff’. Unlike a lot of people who come into cinema, I was not a movie buff. I would rather be reading books or listening to music than watching a movie. But then, I had a lot of juniors from school who had gone on to study videography, Film-making and design and I kept hearing from them about this medium that allows you to do soo much. That allows you to write, that allows you to work with moving image, with music, with dance, with color and all of these were my passion. I used to dance, I was into music, I was a singer. So I got to know broadly, vaguely, rather, that there was this one medium that I could bring all my passions together, that was the only reason I chose cinema. It’s only when I came to Bombay and started trying to get work is when I started watching films to see what is it that I’m getting into. And slowly the medium started blowing my mind because there’s so much you can do with this medium that other mediums cannot allow because this brings together all kinds of expression and you’re only limited by your own imagination. You’re not limited by the medium, really. So, it just just happened by accident. I really didn’t plan it or intended, and I was not passionate about the medium. It happened slowly.

TF: Did you have some sort of a plan? You started off making short films, right? So did you think, okay, I’m going to make some short films and then sort of get a feel for what the industry is like? Or did you actually just decide, okay, I’m going to make a feature film and see how that turns out?

DM: Neither, you can’t. Bombay is a very difficult city to survive as an artist because it’s the financial capital of India. It’s not really an artistic city. It befuddles me, to date, why the film industry is located in a city like Bombay and not, for example, a city like Delhi, which is a little more art oriented, although it is politically oriented as well. So no, I didn’t have a plan. I came to Bombay not even knowing what this medium was like and what I’m getting into. You know, you come to whether it’s a job or I mean, whether you’ve been hired for a job or you just come to explore a certain way of life. You have a certain idea of a timeline in your head that, you know, two years, three years, four years, you’ll make a film and you’ll know what it’s like and you’ll thereafter chart a course for yourself. So I came to Bombay nearly 20 years ago thinking that how long will it take me to make a film? Two, three, four years. So I came and I started. I didn’t know that I have to assist filmmakers because we are also a disorganized industry compared to the American industry, which has a certain sense of organization, which has some semblance of a ladder, you know that you get in at a certain level and after a certain time you write a few films. Four years, six years in, you might make an independent film that will premiere at Sundance. Then you’ll get a studio offer – that is some idea of a roadmap. Bombay doesn’t have that because we’re not organized.

I assisted on a couple of films and then I thought I was ready, and when I thought I was ready was the beginning of 2006. And between 2006 and 2016, in those ten years, I had 17 shelved films. I had films I had written and found producers for that got greenlit, I attached actors to. Some got to pre-production and got shelved. One of them was 80% shot and got shelved in 2009. All kinds of things happened on all those films and these were all feature films, I never considered making a short. So, after 17 shelved films and ten years I was at a strange crossroad where I thought that, you know, maybe I’m not cut out for this. Maybe there’s something that I’m doing wrong. That’s when I started making a lot of short films.

Around 2015, there was a strange portal that opened up and by portal, I mean, a cosmic portal, not like an online portal, opened up in the cinema space in India, where suddenly there were short films being banged out on YouTube and going viral. Something shifted and I’d never considered making short films, but I thought, you know, 10 years of my life and I’ve got nothing to show for it. And I’ve got many stories and I’ve made contacts with people who believe in me so I just pulled friends together. Like a DOP would come in with his own camera, actors came in for free. and I started banging out shorts. I made five shorts in one year. One of them was Taandav and all of them went viral. And suddenly in 2015, I was being pipped as the short film King of India, and I didn’t plan that. I was just trying to compensate for 10 years of 17 shelved feature films, and those 5 short films sort of changed things for me. They led to the film Ajji, Ajji led to the film Bhonsle and Bhonsle led to Joram, so it was a reversed journey. Actually, I didn’t plan it. I didn’t expect that I’d take so many years to arrive at my first feature film that got made and got released. So I say this often to a lot of my friends and my team that in 2003 when I landed at Dadar Station, if I had met a prophet and if he had told me that, you know, your first feature film will release in 2017, 14 years from the date that you’ve come to Bombay, I would have caught the next train back, I wouldn’t have hung around.

TF: You have written and directed all your films so far. Do you feel it is easier to direct your own script? And have you ever considered directing someone else’s script?

DM: I get asked this often. I get offers as well, but I am primarily a writer down in my core, I’m a writer. Even with a film, the film starts forming in my head and starts finding its voice and its rhythm and its personality and its tone in my writing. So, if I have not written it, I don’t know how to direct it. Of course, there are enough directors out in the world who do that. But I also realize that all the filmmakers that I was drawn to from Inarritu, who you mentioned, to Kieslowski, to Godard, to a lot of the masters, were pretty much their own writers. Even if they had other writers, they led the writing of the film. The film really formed itself from the ground up, from the writing. So I’d like to consider it, but I don’t know if I’d be able to do it, and I don’t know, if I’d enjoy it. I’m not a filmmaker first, I am a writer first.

TF: Do you feel like it’s a bigger challenge to direct someone else’s thinking and their vision, you know, bringing their vision into the screen?

DM: No, I don’t know if it’s a bigger challenge. It’s a technical job. It’s like being a cinematographer or an actor or a sound designer or an editor. You’re coming in on someone else’s vision and then you’re trying to bring it to life in a certain way. So I’m a storyteller. I have lot of stories inside me. I’ve got 17 ready scripts that I don’t know if I’ll get to make in my lifetime. And I’m sitting on 140 story ideas, so I don’t know if I’m interested in bringing someone else’s idea to fruition. I’m more interested in my own ideas. So being a storyteller, I don’t know if I want to be a technical hand on a film.

TF: The journey of making a film starts with a script and ends with the audience watching it on the big screen. There are a lot of people, time and money invested into making a film. It is like putting pieces of a puzzle together with the hope that they all fit well. Which piece in your opinion, from your own experience, is the hardest roadblock you had to overcome?

DM: You know that’s interesting you ask me that because every two years my answer to this question has changed because you reach a different stage in your filmmaking career and you suddenly realize that what you thought was the greatest challenge in your last film is actually not. There’s a bigger challenge that you’re facing with this next film, which is slightly bigger in scale and has, you know, more collateral and more risks and more people you need to handle. I finally found the answer to this question a few months ago in something that Guillermo del Toro, the director of Hellboy, Pan’s Labyrinth and Shape of Water said in an interview. He said something very beautiful that summarizes something that all filmmakers across the world face, but we don’t have the right words for it. He said, “A filmmaker, while being a very introverted and inward looking and contemplative and gentle and artistic and emotional creature, because we have to protect our story and our characters, we need to feel”. If you don’t feel we can’t make our collaborators feel and we can’t make the audiences feel. Simultaneously, every second of our lives while we are being this, we also have to be hard and brutal and manipulative and aggressive and almost warrior like to protect the vision of our film from interfering producers or actors who think they are the reason the film’s gotten greenlit and they have counter opinions to yours, all kinds of people who have fertile minds and have strong opinions. But, you have a vision and you need to protect your vision and you can’t always confront them aggressively. Sometimes, you have to be manipulative, you have to lie, you have to connive because you’re trying to protect your film. So, you have to be these two very different personalities all at once. You have to be schizophrenic for life. That probably is the biggest challenge we have to face and not actually let that affect our normal behavior.

TF: As you probably heard, using AI to write scripts is a hot topic with the ongoing writer’s strike in Hollywood right now. Do you think this is something to worry about for Indian filmmakers specifically in the indie/festival circuits, maybe not now, but in the near future? It does not have to limited to just the writing aspect, it can also affect actors as well. So, what is your take on this technology taking over filmmaking?

DM: Yes. It’s something that’s been causing sleepless nights to writers across the world. And it’s not like in India people haven’t tried that. I’ve heard that at least in the advertising world, advertising scripts, they are trying it because advertising scripts don’t really need to have an author or fingerprint as they are just written to maximize product visibility. So yes, it’s a matter of time before producers and studios try to circumvent writers because AI is fairly developed. But, I don’t know if that is not the natural progression of things. You know, even when cinema was invented 125 years ago, not more than that, there must have been a lot of hue and cry that, you know, theater is going to die and live performances are going to die and we can’t do this. We can’t replace live performances and human interaction with, you know, recording for posterity. So there’s always been pushback. It’s human to pushback against technology that will replace human beings. Now, when you look at the industrial revolution, it continues to replace manual labor and trade unions over the last 150-200 years have been up in arms about being replaced by machines. So it is par for the course. As human beings, we are constantly going to upgrade technology. Technology is going to constantly replace human beings. What do human beings do? We innovate? We come up with new ways to make the medium so human independent that you cannot keep up, technology cannot keep up. Do we have a solution yet? No, not really. But I am expecting that in the next 10 to 25 years, something will come up and we will arrive as a new medium. It won’t be cinema as we know it anymore.

TF: You have made 8 short films and 4 feature films. Each film caters to a very niche audience. Every one of these films touch upon topics/issues that people in our Indian society will never openly discuss nor would they want to watch them on the big screen. So, how does this motivate you as a filmmaker to continue telling such important thought provoking stories and push the boundaries of cinema to create that awareness and education?

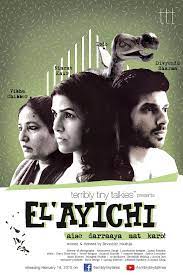

DM: Many answers to that one question. One, I am deep down, I am actually a political activist. If I had not chosen the medium of cinema, I might have been out there either doing activism on the streets or having started a political party to counter the the hegemony of the fascist ruling party. I would have done something of that sort. But I realized very early on that I don’t have those chops. I have the chops of a storyteller or an artist, and there’s so much rage inside. It was but natural that I would channel that into my chosen, what I call a weapon of choice. My weapon is not the protest placard or a gun. My weapon of choice is my story. So I’m going to use that to the hilt. But number two, I mean, yes, my films end up being niche, but I don’t intend them as niche. If you see Taandav and I’ve made a comedy called El’ayichi, a short film and even Joram. In fact, Joram has been an attempt to actually a slightly massier film. It’s a thrilling, it’s every minute something’s happening in the film, it just doesn’t let up. So I try to actually expand beyond the boundaries of niche and rein audiences in that wouldn’t otherwise politically agree with me in a dinner table discussion. I try to entertain them or just thrill them or just get them to sit up and feel something and then slide my politics in. I realized earlier on that today we live in a slightly much more woke and engaged and fertile and awake and active society than we did 20 to 30 years ago. Lines get drawn that much quicker. People have realized what their political stance is by the time they’re teenagers. So I can’t make divisive films in today’s time. So I need to, even though I have a strong political voice, my storytelling and my choice of genre and tone needs to be inclusive, needs to be embrasive. It needs to be welcoming so that dialog can happen. So with every film, I’m trying to expand my audience set wider and wider and wider. So, I hope my films are not niche and will get watched more and more with every passing film. With Joram, that’s actually been the hope and the attempt.

TF: You have worked with some very talented actors in both short and feature films. Some of the big names include Manoj Bajpayee, Abhishek Banerjee etc. How easy or hard was it to convince them to act in your films and did you write any of your scripts with these actors in mind?

DM: No, I never write a script keeping anyone in mind. It takes years for my films to get made, so I can’t pin my hopes on one person. Like with Manoj, for example, the first time we met was for Bhonsle. I was already trying to make the film for three and a half years before I met him and it had stopped, started and stopped and started and stopped three or four times. And then I met him and I had never imagined him as Bhonsle. And then over the two, three years that he and I had to take to set up the film together because it was a difficult thing to find funding for. I started rewriting it and reshaping it to sort of incorporate his personality, and he started working on it too. So it became collaborative after I met him. So, it’s a two way thing. Now with the other actors, like my short films have Nimrat Kaur who was in The Lunchbox. They have Abhishek Banerjee. They have Rasika Dugal who became an OTT star. I worked with all of these people before they became big. Like Abhishek was in a short film called Agli Baar back in 2015, and then I cast him in Ajji as the villain, and then he got cast in Paatal Lok and things exploded for him. So often it’s really the actors that I’d find something interesting in, and we sort of find a great collaboration and things open up for them. So, the only person who was already a huge success before I worked with him was Manoj.

TF: In a perfect world, if you could cast any actor you wanted, who would that be?

DM: I would use AI. Honestly, I can never write for actors. I have a shortlist and then whoever is willing and able and fits the budget and is enthusiastic enough and aligns himself or herself with me. I run with it.

TF: In Taandav, the short film where Manoj Bajpayee plays the lead role of a cop, you end the film with a quote that says “Man is free at the moment he wishes to be”. Towards the end of the film, we see Manoj Bajpayee sort of giving a wry smile when his family is watching his dancing antics on the internet. Did he actually become free or was it all just a Tamasha in his mind as he knows his freedom is only temporary? It also resonated well with what you mentioned in an interview before that making short films gave you a lot more freedom and control.

DM: You know it’s beautiful that you connected those two dots that quote in the film and the impulse to make a film like Taandav came from my driving almost suicidal hunger to make something that I want to make and it must have come, now that you mention it, these things lie in the subconscious and only the audience, an engaged audience catches the filmmaker’s subconscious. Because we while making it, if we delve into what we feel deeply, but we don’t know how much is lurking in our subconscious. So, maybe those ten years and all of those films getting shelved and soo many people telling me how I should be doing that, what I should be doing. I had at least a thousand people sit me down in those years and give me endless amounts of advice that, you know, you might be doing something wrong. Make a big film with a star, sell your soul once and then come back and do this. And you don’t do it like this. You’re too stuck up and you’re being too, you’re too angry. I’m like, Yeah, okay. But just if I hadn’t had 17 shelved films, would you still be saying these things to me? So somewhere all of that maybe came out in Taandav because we tried to make Bhonsle, Manoj and me, and it didn’t materialize. And then when I made four short films, it was him who told me that Why aren’t we making a short together? And I’m like, Wow, I didn’t know that you would want to make a short, and he had seen my shorts and he had a lot of faith. And I had this idea of this cop just exploding inside me for many years because it was really me exploding and it was my catharsis. So, somewhere all these dots sort of joined and what that cop inside Taandav must be feeling at that point, I’m not really sure because it’s a mix of a lot of things. Yes, he did finally say Fuck you to everybody and just danced with a gun in his hand, but at the same time he got suspended and that little girl is not going to go to the school of his wife’s choice. So, he still has to grapple with those demons. So, it’s freedom for today, but he still has to grapple with tomorrow. And freedom is an inch by inch acquired thing. You don’t get eternal freedom all at once. Like what you have today. You might not have tomorrow.

TF: We, as human beings, are shackled by different systems that govern our lives. You have the law and order system, the political system, the education system, the societal system (which includes class, caste, race and various other subsystems) etc. It sometimes becomes hard to get away from these systems, and most people are happy living their lives being controlled by it. But your films Taandav and even Cheepatakadumpa show people who are trying to break free from some of these systems and they are doing so out of frustration or for the plain reason to just be happy. How did these systems affect you as you embarked on your filmmaking career back in 2008? Also, now that you have made four feature films, do you think you have broken free of these systems, especially the ones governing the film industry?

DM: No, you know, as long, especially in today’s time in India when, like I said, the political lines are so strongly drawn, whether it’s religion or caste or class, they’re getting drawn deeper and deeper currently. And even if it wasn’t the case, there is no way to escape this even within the industry, as long as you’re choosing to tell stories that people actually don’t want to hear. And even if I mean, yes, I like I said, I sort of disguised them in the garb of accessibility, whether it’s comedy or thrill or revenge. But, ultimately, I’m saying certain things that I’m holding up a mirror and reflection is ugly. And most viewers don’t want to look at that ugly reflection because life in India and a lot of countries, not just India, is their daily life is really hard to get through it. And the lower you go in the social hierarchy, it’s that much harder to get through your daily lives. So, do you really, when you’re watching a film or reading a story or listening to a song, do you really want to be reminded every time of how dismal and difficult your life is? Maybe not. I understand the need for escape, but I have too much rage inside me to give anyone escape, even if, like I said, the garb will be entertaining, incited, I will catch you unawares and I will shove that bitter pill down your throat because that’s now my mission for life. Otherwise I will self-destruct. And I am bothered by all these things constantly.

TF: And there are a lot of films that are made to sort of escape anyways, right?

DM: YES!

TF: It’s way too many, I would say, especially since the pandemic with the all of the streaming platforms that are just crunching out films almost every week.

TF: Your new film ‘Joram’ is about a father who is on the run with his little baby girl as his past catches up to him. How did you come up with the idea for this film and why is it important for you to share this story?

DM: So, the politics of the tribal condition in India and now that we’ve screened in Australia and Africa, it was already evident to me that the indigenous across the world are facing pretty much the same issues for a few hundred years now. But what is different with India vis-a-vis the Aboriginals in Australia or the Indigenous Red-Indians in America, is that here it’s our own races and our own countrymen who are doing this to our own countrymen. It just flummoxes me. I’ve traveled the tribal areas of Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and Orissa about 12 to 13 years back. I had gone there, really, I was trying to tell stories around the situation from the things I had read, the things I had heard. And even after conversations with journalists who had been on the field, it didn’t feel like enough. It was all intellectual, it was all information. And yes, you can fabricate stories with information and data, but I wanted to move people. I wanted to shake people up and make them think about these things that they choose to not think about. So I traveled. I went and experienced what I could firsthand, and whatever I saw and whatever I heard and whatever I lived through, I think gave me enough stories for the rest of my life. So I’ve been telling these stories for the last 13 years.

My first film Oonga, which then I converted into a young adult novel that won a whole lot of awards. My short film that released with Cheepatakadumpa called Cycle, a lot of my short stories in my book, Forgetting, all these stories have to do with that situation of development, mining and not giving the tribal their rights and forcibly evicting them from their land. So, Joram was an attempt to try and tell this at a scale where I could reach, like I said, you know, not niche audiences. but the wider audience, not as wide as a Shahrukh Khan or Salman Khan audience, but much wider than any audience that my films have accessed so far. So that this conversation, which is not hard enough, not hard at all, in fact, can be hard because especially under this government now, nobody wants to have a counter development conversation. Everyone is being made to believe that roads and dams and rampant construction is the way forward, is the way to progress. And trees don’t matter, tribal lives don’t matter.

So, I’m just trying to ensure that conversations don’t die. So, this was the initial impetus and Manoj Bajpayee standing alongside me and ensuring that a film like this get greenlit and it took us years. Bhonsle took 6-7 years to get made. This he read in 2016 and only in 2021 when he had Family Man behind him and he’d become this huge OTT star that he could take this script to a Zee studio and say that I want to do this with Dev. And the studio came in and a studio that big would have been inaccessible for a filmmaker like me otherwise. You have to take it that far and that wide at a certain scale.

TF: Compared to your previous feature films, you have Zee Studios backing your film this time with Joram. How did your collaboration with Zee Studios transpire and what are some of the lessons you learned working with one of the biggest studios in India?

DM: Now, the interesting thing about Zee studio is that it’s a distribution studio first, and one of the biggest challenges of independent filmmaking in India and the world is that when you’re trying to make maybe that first independent film, you take loans, you sell everything you own, you murder somebody, you rob a bank, you know how to make it. You somehow make that film, but you don’t know what to do with it once it’s made. The biggest challenge we face is distribution. So, suddenly here was a studio that aces it’s distribution and has distributed all kinds of films for decades. I knew that part of the pipeline is covered and I’ve never been in that situation in my life. Because I make a film, then I don’t know when and how it will get out there, if it gets out there, will it reach an intended audience? If it reaches the audience, will the audience even watch it completely? You don’t know the answers to those questions. Here, suddenly I had the answers to those questions. But, I needed to recalibrate what I’m making because Zee studios are going to get me that kind of access, I actually can’t then make such a niche film that it sort of makes Zee studio question why they backed a film like this in the first place. So, it was a collaborative creature after it got greenlit, I went into rewrites while we were setting up the film and we sort of consciously and I’m asked if that was a compromise, and I called it a recalibration. I always work backwards from the opportunities and the pieces that I have before me. Now I had Zee studio and I had Manoj Bajpayee and I had distribution. So, I’m obviously going to calibrate what I’m making. I’m going to try and see how can I maximize this because also every film I have made takes me 3 to 4 years to set up. And I’ve been in Bombay now 20 years, I have 17 shelved films. I don’t have the luxury of waiting 4 or 5 years to set up each film, so I would need every film to open up doors for me once it’s made. So, that was one of the biggest learning curves that I went on with this film, how to access, how to sort of work and do my skill, that sense of scale.

TF: And like you mentioned, I think one of the hardest pieces of making an independent film is making sure that it reaches as wide audience as possible, right? So, that is one of the one of the biggest challenges. What is your opinion on the state of independent cinema in India today? Especially since the pandemic? There are way too many films coming out that people don’t even have the time to sit and watch commercial films. How does that affect independent cinema and do you think India is actually doing a very good job in sort of promoting young indie filmmakers?

DM: It’s a complex, complex, complex answer. I don’t have any simple answers to that. There are many facets to this. Firstly, Indian cinema compared to any other country’s cinema is not just one cinema, it is 28 cinemas plus Hindi cinema. And every regional cinema is almost like an individual independent entity that has its own cultural and artistic quirks. Like, you cannot compare the independent voice or texture of a Marathi film with an Assamese or Malayalam film. They are so different that they could very well have been made in different countries. So given that very exciting heterogeneity, how does one country actually know what to do with all these cinemas? So, that’s where we actually hit roadblocks and that’s always been the case because in the past Malayalam cinema has been sort of buffered from Hindi cinema. Hindi cinema audiences have not been able to access Malayalam cinema, for example, like you yourself, you had to go to, you know, video parlors to see what foreign films are there. Now the regional films from India won’t even make it to the Hindi speaking audience until the online YouTube and then OTT boom happened. So, the positive side is that suddenly you have access.

And so when you have access, of course you will have more than you can watch because suddenly now you can watch all these 28 different languages where earlier you were only watching one language sitting in the Hindi mainstream. So the downside to that is now there’s a glut and you can’t choose. But I see that as a temporary positive that, yes, now you at least have the access. Now it’s up to you to as a viewer to find and hunt down the good cinema. Now, the downside to that is how many people have the stamina to do that. Then it comes to the budget, like even if my film Ajji was on Netflix, a Netflix will not spend a single paisa putting any algorithms to make Ajji visible because nobody wants to watch it. People want to watch the last big blockbuster like an RRR. So, they will put money in the algorithms to push RRR onto your feed, so Ajji will not be on your feed, you will not even know Ajji exists. So there are those downsides, but there are those upsides to that now you have access. You don’t need to go to that film festival once a year to watch those two regional films that you would otherwise not get to watch. It’s a very tricky conversation.

TF: Tricky? Yeah. It’s just that when you have so many films to choose from and then out of that one is an independent film, like what is the likelihood that you would want to watch that independent film as opposed to maybe 4 or 5 of the commercial blockbusters or something of that sort? It sort of depends.

DM: Look at the flipside, till ten years back, that independent film didn’t even enter your setup. At least it’s there and you are choosing to not watch it.

TF: What are some of the directors from Indian and World Cinema that have influenced you over the years?

DM: So, like I said, I have never been a film buff. And even today, like if you ask me, have I watched RRR or Pathan or Jawan or 10 other independent Indian films? I have not watched any of them because I watch about 10 films a year. I really curate my list. I watch them slowly. I watch them in pieces, like reading a book. I’m a very different film watcher. I don’t enjoy watching films in theaters. I like taking a film apart and really trying to know what in it worked for me or what didn’t. So, film watching has not really been a big part of my shaping of my artistic voice. I don’t really have influences. Maybe I do, but I wouldn’t be able to pinpoint them because I’ve not watched any filmmaker’s entire filmography either. Like a Kieslowski. The few films I have watched of his have had a profound impact on me. I have not watched them again and again or watched all his films to say that he’s influenced me, for example. So it’s really art and graphic novels and music. It’s like when I went to Cannes in 2018, I spent all of three days in the festival, but I spent four days in Paris, of which two days I was in the Louvre. I just couldn’t leave Louvre. Those are my influences.

TF: What is your advice to upcoming filmmakers especially in the indie space?

DM: I generally, again, I don’t like giving advice because when I was given advice, I used to never listen to it. It is a double edged sword because sometimes you’re a little lost like I know I was for many years and you think you’re not doing the right things, which is why you’re facing failure again and again and you’re hoping that someone will tell you that one magical thing that would just unlock the mysteries for you. But 9 out of 10 times that one magical thing would have worked like magic for the person giving you that piece of advice. And there’s a remote chance, or maybe not at all, that will work for you. And you actually take it seriously and you implement it and you’re like, Dude, you’re going to work for me and you didn’t. So the only advice I actually give is that don’t take advice and learn from your mistakes. If there’s something you want to do, whether it’s singing songs all your life or making films, just start doing it right now, don’t wait for the right moment.

I will give a little anecdote here. I might have gotten the facts a bit wrong because it’s a second or third hand anecdote and it’s from many years ago. So, Stanley Kubrick back in the 70’s was the god of the artistic independent cinema in America. And everybody, every student of film wanted to listen to Stanley Kubrick and what made him and why he makes the choices he makes and they wanted Stanley Kubrick’s advice. So, finally, I think, if I’m not mistaken, he got frightened and he finally told the New York Film School, you know what? I’ll come. So, I’ll just give that one meeting to all your students and whoever wants to be there better be in that hall that one time. So, he comes and word has spread like wildfire. And I think some three, four, five, six, seven, ten batches of students, thousands of students packed into that one hall to listen to Kubrick. Kubrick walks on stage and he says, “How many of you here want to make a film and haven’t made a film yet?” And all hands shoot up and he says, “Pick up a camera, go shoot your film”, and he leaves. That’s all he had to say. You will make one bad film or make two bad films but you will learn from it, it will be your journey.

TF: If you could go back in time when you started making films, would you change anything and what would you do differently?

DM: Fuck, that’s you know, that’s a very triggering question because like I said those 1o-12 years that my films weren’t getting made and now I’m suddenly on the cusp of being recognized for my films because Ajji and Bhonsle had a very niche audience. It’s Joram that’s actually started expanding my audience and is traveling wider than my earlier films did. I’m in my forties. I expected this to happen to me in my late 20’s because when I first heard of Shyamalan and Sixth Sense and I saw Sixth Sense and it blew my mind and I realized he was 29 when he made it. I’m like, okay, I can make my first insanely good film at the age of 29, if Shyamalan could do it. I’m in my forties and my films are just starting to get recognized. So, if I could go back and change something, I’d probably not come to filmmaking at all. I would stick to writing because I think I’m a pretty compelling prose writer. But in my endless quest to make my films and all these years of failure, not failure, but thwarted attempts, I never gave time to my prose writing and the one novel I wrote, I won the two top awards that year for young adult fiction. So, maybe I would be sitting on ten novels right now. Maybe, I would have won a Booker. I don’t know, I may have not come here at all.