Let’s talk about Steven Soderbergh. Now and then, the director hits the right niche, packing theaters with his Ocean’s trilogy or giving the role of action hero to an actual action hero with Haywire. But more often than not, Soderbergh’s films are quiet little experiments that most moviegoing audiences miss. Cinephiles may take that as a point of pride, a well-kept secret, but, with the director claiming that someday soon he’ll retire, it’s about time he gets a little more recognition. I won’t be breaking new ground here, lauding The Limey as one of the great unsung action films of the 20th century, but, having finally watched it, I realize it’s the sort of film I can’t avoid discussing.

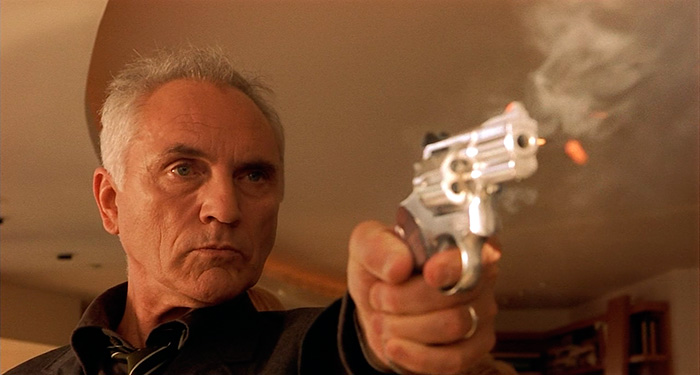

The Limey was Soderbergh’s followed up his pre-Ocean’s Eleven crime film, Out of Sight, a slick action film that was both a box office hit and an infinitely watchable film. One year later, The Limey came out. The film failed to make back even a third of its budget in international sales, relegating it to the lesser-knowns pile with Bubble, Schizopolis, and other Soderbergh films you are now googling to see if they even exist. But while Out of Sight had the star power of George Clooney and Jennifer Lopez and earned big at the box office, it only hints at the genre experimentation that has defined Soderbergh’s career in the 21st century. That experimentation comes to fruition in The Limey, and it required a solid action film framework for Soderbergh to play with. From the first line of the finished film, the director veers off course from Dobbs’ script, starting a feature-length time jumble throughout which sound and scene are often disconnected and information is pieced together by creating a patchwork of time through which snippets of conversation form the puzzle Wilson (Terence Stamp) is trying to solve.

The constant jumble of time and space, confusing where and when we are experiencing diegetic information, creates a sort of stream of consciousness siphoned through the investigative mind of the main character as he attempts to solve the murder of his daughter. The first lines, “Tell me. Tell me about Jenny,” hint that the rest of the film is a long rumination on the events of Wilson’s journey, looking back during the return flight to England on the evidence. There are certain moments when we see the narrative through other eyes, true, but this is only to keep the audience focused on Wilson’s self-examination instead of asking questions about the plot.

What Soderbergh proves with The Limey is that an action film doesn’t have to lose steam to gain humanity. Instead of throwing in a short scene or two where Wilson deals directly through dialogue with his role in his daughter’s life, the accumulation of his memories defines the character and his motivations for us. A lesser director might overload those scenes, making the evolution of the character clunky and forced, seeming like a necessary evil shoehorned in between the action. But Soderbergh makes the cuts between memory and scene part of the action, keeping a fast pace while rounding Wilson out in small doses. Would the film have worked without Soderbergh’s overhaul? Dobbs gave us a great character in Wilson, likable, quick, and fun. But while that character might have driven a summer action flick, Soderbergh’s exploration into human motivation gave us a contemplation on revenge and loss. Not to mention what may be the best action film of the nineties.

So how does he accomplish that mix? Through flashback and the ingenious use of clips from Poor Cow, a 60’s film starring, again, Terence Stamp as a criminal named Wilson, Soderbergh fills out the character, giving him the sort of depth we don’t find in the common action hero. This allows us to focus on the relationship between father and daughter rather than a simple man-versus-world plot. Short scenes of a younger Jenny on a beach in England, in a time before Wilson went to prison, appear like clips of a dream, overlaid with Wilson’s soft humming of a song. While Dobbs script uses the death of Jenny as a vehicle for revenge, Soderbergh’s revisions make her a ghost, haunting what could be an adrenaline trip like The Transporter and making it instead a contemplation on lost time accompanied by a still action-packed flick.

Sure, sometimes a director’s reliance on the script means great things (think No Country for Old Men with its strict adherence to the novel to recreate the McCarthy tone). But as often, a great director can be bogged down by a subpar script (every other Clint Eastwood film, which, as a huge Clint Eastwood fan, is a real bummer). Soderbergh’s ability to reimagine a basic action script made The Limey an action film about the motivations of action film characters. Had he ended with Wilson declaring his next revenge plot, the first would have been meaningless. Instead, Wilson accepts what happened in the past, realizing his mistake in choosing a life that meant losing time with his daughter. As he pursues Terry Valentine (Peter Fonda), he processes his experiences with Jenny and his wife, long dead, and tries to make the act of revenge a solution. At the climactic scene, Wilson walks away, leaving Terry alive. The scene is the same in the original script, but here it is imbued with more history. Instead of being a simple twist, Wilson’s action is the only logical option as he finishes processing his relationship with his daughter.

Whenever Jason Statham appears on screen, I quickly forget there’s a human being somewhere in that character (except in the woefully underappreciated–in my useless opinion–Revolver). Most action heroes are little more than tour guides for explosions and vehicles for butt-kicking. With The Limey, we still get the action we want, but, at the end, there’s the nagging feeling that maybe Wilson is a human being too, and that’s the sort of action hero I want to revisit. I don’t fantasize about becoming him like I might with any of Dwayne Johnson’s unbelievably masculine characters, but I empathize with him, and if I don’t go to the movies to feel something, I don’t know why I go.