Wes Anderson is, without a doubt, one of the most distinctive, unmistakable auteurs of contemporary cinema. From the meticulous symmetry of his framing to the carefully curated color palettes and the almost melancholic tone of his ironic humor, everything about his style screams his name. Films like Moonrise Kingdom (2012) and The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) established a visual and narrative language that has inspired (and oversaturated) many imitators – yet none have managed to replicate it with the same precision. Even though his more recent work – like Asteroid City (2023) and The French Dispatch (2021) – left me somewhat indifferent, my curiosity to see each new project remains intact. The Phoenician Scheme doesn’t change the writer-director’s style in the slightest, but it strikes a more accessible balance between his elaborate aesthetics and a straightforward narrative.

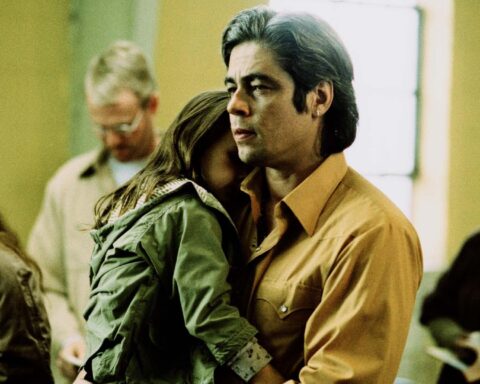

Written and directed by Anderson himself, The Phoenician Scheme tells the story of Zsa-zsa Korda (Benicio del Toro), a European magnate in the arms and aviation industries whose life has seen it all – from surviving half a dozen plane crashes to fathering ten children with different women. His daughter Liesl (Mia Threapleton), a nun living in seclusion, is unexpectedly drawn into her father’s shady business dealings. Joining them is Bjørn (Michael Cera), Liesl’s tutor and loyal advisor, who embarks with the two on an unlikely journey through European capitals and secretive locations in the Middle East. As the mysterious scheme that gives the film its title begins to take shape and threatens global geopolitical stability, the trio finds themselves caught in a web of corruption and power games that transcend diplomatic, corporate… and familial borders.

Despite maintaining the usual long monologues, stylized dialogue, and impassive facial expressions, Anderson delivers in The Phoenician Scheme a more direct story than usual, with a clearer goal: the reconciliation between father and daughter. This dramatic anchor gives the movie a palpable thematic layer that’s not always as present in his past work. Korda, initially introduced as yet another of the director’s emotionally distant creations, slowly reveals layers of remorse, guilt, and a longing for redemption – all explored with dry yet effective humor that makes his arc more engaging.

The performances, as expected, are all top-notch. Benicio del Toro (No Sudden Move), with his commanding charisma, delivers a controlled yet deeply layered performance, conveying his character’s gradual inner transformation with subtlety. Threapleton (The Buccaneers) proves to be a true revelation, handling the dense dialogue with impressive ease and showcasing excellent chemistry with del Toro. Cera (Barbie), meanwhile, fits perfectly into Anderson’s universe, blending his trademark awkwardness with impeccable comedic timing. The dynamic between the three leads is one of the film’s strongest pillars.

Visually, The Phoenician Scheme is everything you’d expect from a collaboration between Wes Anderson and his longtime production designer Adam Stockhausen. This department is, once again, extraordinary: perfectly symmetrical sets, pastel tones mixed with vibrant colors, theatrical environments that create a feeling of an encapsulated world… Every frame looks like an illustration from an old storybook – something the filmmaker has always aimed for and continues to execute masterfully. Alexandre Desplat’s music, another frequent Anderson collaborator, maintains a quirky, whimsical tone, functioning almost like a parallel narrator that enhances both the comedic and dramatic moments. It’s a score that knows when to shine and when to pull back.

Another technical highlight is the presence of Bruno Delbonnel (Darkest Hour) as director of photography. Though it’s his first collaboration with the American filmmaker, Delbonnel fits Anderson’s style like a glove, preserving the lateral camera movements, quick cuts between static shots, and flat lighting that enhances the charming artificiality of the settings.

Thematically, The Phoenician Scheme delves into issues of family reconciliation, ego, and communal identity. Korda’s character represents the archetypal individual who, after a life filled with egocentric decisions and superficial motivations – fame, money, prestige – finds himself faced with the emotional void those achievements left behind. The reunion with his daughter, in a context of international intrigue and corporate espionage, ultimately serves as a metaphor for a return to forgotten values. Liesl, on the other hand, symbolizes a generation demanding authenticity and emotional accountability – even in the face of parental mistakes.

That said, the decision to keep the characters’ expressiveness in a restrained, almost indifferent register may continue to alienate some viewers. Emotional detachment is undeniably a hallmark of Anderson’s work, but when the comedy misses the mark – as was the case in parts of The French Dispatch – that coldness can come across as disinterest. However, in The Phoenician Scheme, the emotional foundation is strong enough to counterbalance that effect. The gradual bond between Korda and Liesl is developed through small gestures and subtle glances which, paired with the sarcastic humor, result in genuinely touching moments.

Finally, while the script remains full of the filmmaker’s signature verbal flourishes, it’s more narratively focused than his recent movies. There’s no excess of subplots or throwaway characters – the story progresses with clarity, and the ending delivers an emotionally satisfying note, reinforced by a last choreographed scene that echoes each character’s growth.

The Phoenician Scheme is yet another clear example of Wes Anderson’s singular vision, with the filmmaker continuing to provide space for every department to shine – from Adam Stockhausen’s extravagant production design to Alexandre Desplat’s witty score, and Bruno Delbonnel’s immaculately aligned cinematography. However, it’s in the thematic exploration where the film reaches a rare point of balance: by portraying the transformation of a man consumed by vanity and ambition into a vulnerable and redeemed father figure, the writer-director offers a genuine reflection on regret, family reconnection, and personal sacrifice. The subtle yet intentional performances by Benicio del Toro, Mia Threapleton, and Michael Cera reinforce that emotional core, bringing humanity to a meticulously artificial world.