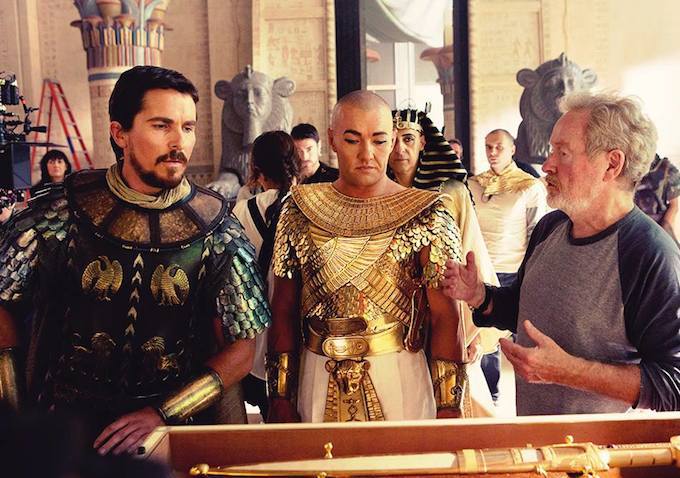

Sometimes Ridley Scott doesn’t make giant epics like Gladiator or Legend and focuses in on relationships between characters, a sin Matchstick Men and A Good Year. But when Scott combines the two, boy do critics get mad. Blade Runner, a sci-fi adventure now regarded as a classic, was poorly received at its opening. All the action of Harrison Ford chasing down renegade replicants was offset by the persistent need to discover who Rick Deckard really was. What we get then is a great action film with a heavy sense of meaning. Scott tried for this approach with his most recent film, Exodus: Gods and Kings, going so far as to devote the film to the memory of his brother, Tony Scott (another director whose best work went unacclaimed (or maybe I’m an idiot and Man on Fire wasn’t the better version of Taken)).

The story of Moses in Egypt has been told and retold, always as a historical epic, an overview of the expanse of Jewish suffering and God’s deliverance. Rarely does a film about Moses vary from the biblical text and Exodus, for the most part, seems to stick to that tradition (though it is interesting to note that many of his changes are in line with Thomas Mann’s The Tables of the Law, and Ridely Scott featured Mann’s Death in Venice in A Good Year and all things are connected and we live in an eternal recurrence) . But the ways that it breaks are important as they raise questions about the biblical truths that underlie the narrative. Now, before we get too far into the changes the film makes, keep in mind that Scott, as a blockbuster filmmaker, does have a certain duty to the audience to keep them entertained, so while some choices veer from the original and challenge the viewer to question their belief system, some are just because we like violence and special effects.

So Moses (Christian Bale) comes to the princess in a basket, gets raised by his sister (unknowingly), kills some guys, gets kicked out, figures out who he is, gets married, becomes a shepard, then heads up a mountain to find some sheep, gets caught in a rock slide, gets knocked unconscious, and sees/hallucinates Malak, a messenger from God, as a child while he’s submerged in the mud. Suddenly we’re not watching the biblical story of Moses. Scott, as he did with Robin Hood (which is the only reference I’ll make to that terrible movie), approaches history with an eye towards stripping away the legend and focusing on the humanity of it. Moses himself is unsure whether he’s following God or hallucinating orders from a brat.

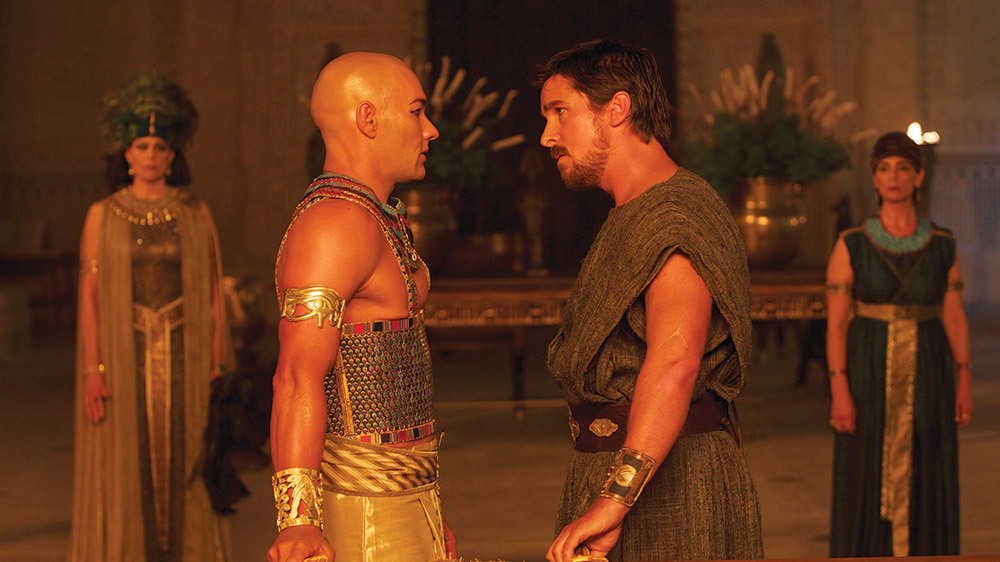

This is most interesting when Moses starts acting as messenger of God to Egypt. Suddenly the Egyptian court is forced to justify the ten plagues sent down, and when they can’t, Ramesses executes them rather than accepting the possibility that the Hebrew god has power. This interplay of faiths is a fascinating point to bring out. Moses at first doesn’t believe in God and never fully accepts the visions he has as more than hallucinations (Joshua’s (Aaron Paul) point of view is the audience’s when he watches from a distance as Moses argues with a deity who’s either invisible to all eyes but his prophet’s or who isn’t there at all). Ramesses (Joel Edgerton) believes he is God in his role as the pharaoh, so when Egypt collapses around him and he is unable to even save his own son, his whole worldview falls apart.

What’s fascinating is Scott’s look at the relationship between these two characters as they struggle to deal with powers beyond their control. This comes to a head in the last act when Ramesses army follows the Israelites to the Red Sea. Moses’ army prepares to fight and, as the audience, we’re prepared for a battle similar to the one at the beginning. But as the waters of the Red Sea fall back across the sea bed, Moses sends his army to shore and Ramesses’ army suddenly seems a little less keen on fighting and they run away. Before the two men can confront each other, the wall of water crashes down on them and sweeps them to opposite shores.

Scott seems concerned with the ability to choose in a world where God exists while simultaneously wondering if there is a God. And if there is, what’s the deal with all the plagues? Of course, Scott didn’t write the film, but his direction is powerful enough to control the tone of the script. While critical reviews for his work have been less stellar recently, Exodus is proof that Scott is less concerned with worldwide acceptance (though the film turned a tidy profit in theaters) than he is with asking big questions. By shaking up a story that much of the world holds in high religious regard, Scott shows his ability to continue making film goers think, whether they want to or not.